The Illusion of Spanish Success

Spain in 2007 looked like a European success story. A budget surplus of 1.9% of GDP, public debt below 40%, an AAA credit rating, unemployment at 7.95%—the lowest since 1978—and GDP growth of 3.8% painted a picture of economic triumph. Between 1997 and 2007, Spain created one-third of all new jobs in the EU-15 despite being smaller than Germany. The “Golden Decade” seemed to vindicate the European monetary union.

Yet beneath this prosperity lurked a fatal imbalance. Housing construction represented 18.5% of GDP. Spanish banks expanded total credit from €559 billion in 2000 to €1,760 billion by 2007—a threefold increase driven almost entirely by real estate lending. In 2006 alone, Spain started construction on 800,000 housing units, exceeding the combined total of Germany, France, Italy, and the UK. Land prices rose 500% between 1997 and 2007, the sharpest appreciation among all OECD countries.

Banks financed this boom through wholesale markets and securitization, creating €243 billion in mortgage-backed securities and covered bonds that qualified as ECB collateral. The cajas—regional savings banks controlled by political appointees rather than shareholders—expanded most aggressively. Loans to real estate developers reached staggering levels: 26.1% of total lending at Sabadell, 21.9% at Banesto, 19.4% at Popular.

When credit markets experienced turbulence in August 2007, Spanish banks appeared resilient due to limited U.S. subprime exposure. This resilience proved illusory.

The Fatal Collateral Squeeze: 2007-2008

The ECB’s response to the emerging crisis inadvertently devastated Spanish banks. While the ECB did provide emergency liquidity when interbank markets froze in August 2007, it maintained strict collateral standards precisely when Spanish banks needed maximum flexibility. High haircuts on asset-backed securities limited their funding utility just as wholesale markets began freezing.

ECB Collateral Policy Evolution 2007-2008

| Year | 2007 Q1 | 2007 Q3-Q4 | 2008 (after Lehman) |

| Collateral Quality | Relatively strict | Slightly more flexible, selective | Significantly relaxed |

| Types Accepted | High-quality government bonds; Highly rated corporate bonds | Some ABS if highly rated | Government bonds; Corporate bonds (broader); Lower-rated ABS; MBS of varied ratings |

| Haircuts/Risk | Lower haircuts for safe assets, higher for lower-rated | High haircuts for ABS and lower-rated securities | Haircuts lowered for riskier assets |

| Impact on Spanish Banks | Cajas with MBS portfolios face higher haircuts; liquidity constrained | Spanish banks with weak collateral constrained despite crisis | Too late—Spanish MBS already impaired by downgrades and price declines |

This timing proved catastrophic. Spanish banks, having securitized mortgage portfolios during the boom, found these securities provided insufficient ECB funding capacity when wholesale funding vanished. Had the ECB eased collateral requirements earlier, Spanish banks might have accessed more liquidity. But this would have provided only temporary relief—perhaps twelve to eighteen months—before deteriorating asset quality forced a reckoning.

When Lehman Brothers collapsed in September 2008, conditions transformed overnight. Spanish banks had borrowed €49.38 billion from the ECB by July 2008—triple the previous year. After Lehman, the ECB did relax collateral rules significantly, accepting broader corporate bonds, lower-rated ABS, and varied-rating MBS with reduced haircuts. But it was too late. Rating agencies were already downgrading Spanish MBS as real estate prices fell and construction firms defaulted. Market prices collapsed as secondary markets froze, reducing even eligible collateral’s value under mark-to-market requirements.

The “close links” prohibition proved particularly destructive. This rule prohibits banks from pledging self-originated assets unless structured through properly capitalized special purpose vehicles representing true sales. Many Spanish MBS failed this test—retained on balance sheets or with operational roles (servicer, swap provider, liquidity facility) creating disqualifying links. Banks suddenly discovered that securities they’d counted on for ECB funding were ineligible precisely when funding was desperately needed.

They faced compounding pressures: rating downgrades below BBB- minimum thresholds, market price declines reducing borrowing capacity even for investment-grade securities, and the close links prohibition excluding expected funding sources.

Liquidity Without Solvency: The Critical Distinction

Here lies the fundamental difference between the American and European responses. The ECB never conducted quantitative easing as that term came to be understood in America, and this distinction explains the divergent recovery speeds.

When the Federal Reserve launched QE in December 2008, it purchased mortgage-backed securities directly, including those backed by non-performing loans. These purchases removed toxic assets from bank balance sheets, transferring credit risk to the Fed. Banks that were technically insolvent became solvent once the Fed purchased impaired assets at above-market prices, allowing normal lending to resume by 2010.

The ECB operated entirely differently. Its Long-Term Refinancing Operations (December 2011, February 2012), providing €1 trillion in three-year loans, were collateralized lending—banks pledged collateral and received loans, but maintained ownership of the assets. The ECB did not buy impaired assets or remove toxic securities from balance sheets. It provided liquidity but not solvency.

Banks receiving LTRO funding still held non-performing loans and impaired securities, still faced capital constraints limiting lending. Cheap ECB funding allowed survival but not recovery.

The Securities Markets Programme (2010-2012), through which the ECB purchased sovereign bonds from troubled countries, also differed fundamentally from QE. The ECB bought performing government bonds in secondary markets, not non-performing bank loans. Purchasing Spanish or Italian government bonds supported sovereign funding but didn’t clean bank balance sheets. The SMP prevented yields from rising further—helping banks indirectly—but didn’t address impaired real estate loans and MBS.

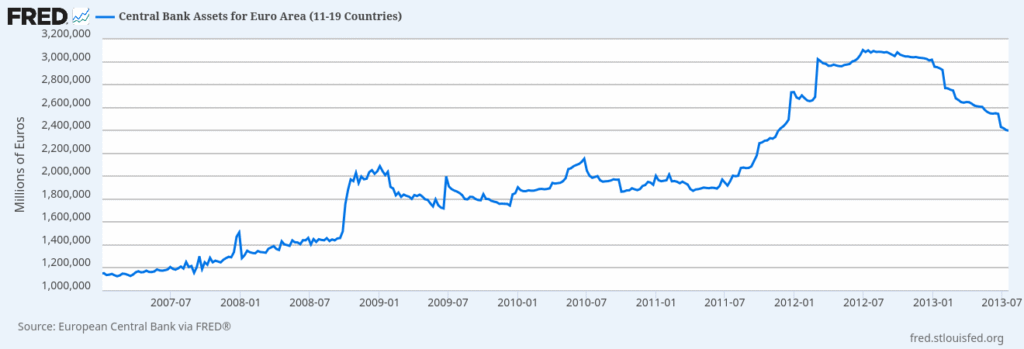

ECB Balance Sheet Expansion Without Asset Cleanup

Key Events:

- 2008: Post-Lehman emergency liquidity (€900bn → €1,500bn)

- 2011-2012: LTROs provide €1 trillion (peak ~€3,100bn)

- 2012: Draghi “Whatever it takes” – OMT announced

- 2015: Full QE begins (€60bn/month purchases)

Despite massive balance sheet expansion from €900 billion (2006) to peak €3,100 billion (2012), the ECB never purchased impaired bank assets. The expansion reflected emergency liquidity via standard repo operations, LTROs, SMP sovereign bond purchases of performing bonds only, and extended collateral eligibility.

This explains the paradox: The ECB’s balance sheet expanded 3.4x, but European banks remained impaired because toxic assets stayed on their balance sheets. The Fed’s balance sheet expanded 4.5x (2008-2014), but American banks recovered quickly because the Fed actually purchased and removed toxic MBS from bank portfolios.

Who Paid: The Decisive Difference

Fed vs ECB Crisis Response Comparison

The fundamental difference between America’s recovery and Europe’s depression lies not in the severity of banking losses but in how those losses were absorbed. When the Federal Reserve purchased toxic mortgage-backed securities through quantitative easing, it created new reserves with keystrokes—a purely monetary operation requiring zero fiscal resources. No taxpayer money changed hands. No budget allocation was needed. American schools, hospitals, Social Security, and Medicare continued operating normally because bank bailouts consumed no real economic resources. The Fed’s balance sheet expanded, but the federal budget remained available for social spending.

In the Eurozone, the ECB’s chose to provide collateral only against performing assets, forcing EU countries to step in basically purchasing these impaired assets to clean bank balance sheets. When Spanish banks required recapitalization, the Spanish government had no choice but to borrow actual money in bond markets—paying interest to private investors—and inject that cash into failing banks. Every euro directed to banks meant one euro less for pensions, healthcare, education, or unemployment benefits. This wasn’t merely a policy choice; it was the mechanism that transformed a banking crisis into a sovereign debt crisis.

| Stage | United States (Fed/Treasury) | Euro Area (ECB/Governments) | Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crisis hits banks | Lehman collapses, huge MBS losses | Global shock + domestic banking losses | Banks severely impaired both regions |

| Immediate support | Fed/Treasury buy toxic assets (MBS, NPLs) and inject capital (TARP) | ECB provides liquidity via LTROs, accepts wider collateral, but does not buy bad assets | US banks clean up quickly; Euro banks remain burdened |

| Loss absorption | Centralized via Fed + Treasury; banks recapitalized, risk socialized | Losses shifted to sovereigns (national governments recapitalize banks), increasing public debt | US: banks lend again; Euro: banks constrained, weak transmission |

| Monetary transmission | Fed cuts rates, QE stabilizes markets, increases reserves; credit flows | ECB lowers rates, conducts LTROs, SMP, CBPP, OMT, but constrained by bank balance sheets; QE delayed to 2015 | US: GDP rebounds faster; Euro: slower recovery, deep recessions |

| Fiscal response | Stimulus (TARP + ARRA), no immediate austerity | Fiscal consolidation/austerity enforced in high-debt countries | US: consumption/investment recover; Euro: GDP stagnates |

| Credit availability | Banks resume normal lending; households/firms regain access | Banks’ NPLs and capital constraints persist; tight credit | US: housing/consumer spending rebound; Euro: weaker markets |

| Overall outcome | Stronger recovery, lower unemployment | Recovery delayed, fragmented; sovereign stress creates secondary crisis | Euro: prolonged recession, slower convergence |

Spain’s public debt exploded from 34% to 100% of GDP not because of fiscal profligacy but because the government was forced to use scarce fiscal resources to absorb losses that the Fed absorbed through cost less monetary operations. Markets, seeing Spain’s debt surge and knowing further bank losses loomed, questioned debt sustainability. Borrowing costs spiked. Austerity became unavoidable. The doom loop was born—and it was completely avoidable had the ECB possessed the willingness to conduct genuine quantitative easing in 2008-2009.

The contrast is stark. In America, the central bank and federal government absorbed bank losses with minimal impact on citizens’ daily lives or safety nets. In Europe, national governments absorbed losses by imposing austerity on citizens. American workers kept their safety net; Spanish workers lost theirs.

Spain’s Response: Too Little, Too Late

Spanish authorities addressed the banking crisis with measures that failed to confront underlying insolvency. In October 2008, they announced €100 billion in guarantees for new bank debt (no immediate cash outlay) and created the FAAF—a €30-50 billion fund purchasing “high-quality” assets, primarily covered bonds, to provide liquidity. These addressed symptoms (wholesale funding difficulty) without confronting the disease (massive unpayable loans to developers and construction firms).

Spanish Public Bank Support 2008-2009

| Year | Policy Action | Amount (€bn) | Nature | Fiscal Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | Bank debt guarantees | Up to 100 (contingent) | Guarantees | No immediate outlay |

| 2008 | FAAF asset purchases | 30-50 | Liquidity provision | +2-3% GDP to borrowing |

| 2009 | Creation of FROB | 9 (initial) | Capital injections to cajas | Direct cost ~0.8% GDP |

| 2009 | First caja mergers (FROB) | ~7 disbursed | Equity/subordinated debt | Fiscal |

| Total (2008-2009) | Mixed measures | ≈ €40-60 (incl. guarantees) | Mixed contingent + direct | ~3-5% GDP exposure |

By June 2009, authorities acknowledged that liquidity support was insufficient. FROB, established with €9 billion in public funds, facilitated mergers among the weakest cajas and provided capital injections. Throughout 2009-2010, FROB consolidated 45 cajas into 11 entities—frequently combining weak institutions with other weak institutions, creating larger undercapitalized banks without resolving asset quality.

Yet non-performing loans rose inexorably. Default rates for real estate developer credit hit 14% by late 2010; construction companies reached 11%. Housing prices that had nearly tripled between 1997 and 2007 fell steadily. By the end of 2011, Banco de España classified €180 billion as troubled assets, with €656 billion in mortgages and 2.8% officially non-performing—a figure widely understood to understate true impairment.

The Sovereign Trap and Doom Loop: 2010-2012

The transformation from banking crisis to sovereign crisis followed inexorable fiscal arithmetic. Government bank support, collapsing tax revenues, and surging unemployment benefits drove public debt from 34% of GDP in 2007 to 52% in 2009, then 69% in 2011. Markets questioned Spain’s fiscal sustainability not due to past profligacy—Spain had run surpluses and maintained low debt—but by projecting ultimate bank bailout costs combined with persistently high unemployment reducing future revenues.

Timeline of Spanish Crisis Evolution

| Date | Event | Debt/GDP | Unemployment | Bank NPLs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 Q4 | Pre-crisis | 34% | 8.0% | 0.9% |

| 2008 Q4 | Lehman collapse | 39% | 13.9% | 2.8% |

| 2009 Q4 | FROB created | 52% | 18.0% | 5.1% |

| 2011 Q4 | Sovereign spreads spike | 69% | 22.9% | 7.4% |

| 2012 Q2 | EU bailout request | 75% | 24.8% | 10.5% |

Unemployment nearly doubled in the first year post-Lehman (8% to 13.9%). NPLs tripled in the same period (0.9% to 2.8%), then more than tripled again over the subsequent three years. Public debt increased 50% in two years (34% to 52% of GDP) despite no structural deficit pre-crisis.

The sovereign-bank doom loop emerged fully in 2011. Spanish banks held substantial Spanish government bonds—traditionally considered risk-free and encouraged by zero Basel risk weights. As sovereign spreads widened, reflecting market concerns about the government’s capacity for continuing bank support, these holdings became liabilities. Rating agencies downgraded Spanish sovereign debt. Under ECB collateral rules, sovereign downgrades triggered higher haircuts on government bonds that banks pledged for refinancing.

Banks faced a terrible choice: sell bonds and realize capital-weakening losses, or hold bonds and accept reduced ECB borrowing capacity.

The feedback mechanism proved vicious. Weak banks required government support, increasing public debt and widening sovereign spreads. Higher spreads reduced the value of government bonds banks held, further weakening the banks. Spanish banks’ ECB funding dependence intensified through 2011-2012. By mid-2011, Spanish banks accounted for over 20% of total ECB lending despite Spain representing only about 11% of Eurozone GDP.

The Counterfactual: Alternative Collateral Rules

Spanish banks created approximately €243 billion in MBS and covered bonds by 2007. Perhaps €150-200 billion were retained on balance sheets or maintained close links through servicing, swap provisions, or liquidity facilities—rendering them ineligible for ECB pledging. Had these been made eligible, Spanish banks could have borrowed substantially more from the ECB during the critical 2008-2010 period, maintaining credit lines and avoiding the sharpest contraction.

Counterfactual Analysis – ECB Close Links Waiver

| Scenario Element | Actual Outcome | Counterfactual (Close Links Waived) | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Additional ECB-eligible collateral | N/A | €150-200bn Spanish MBS | +€150-200bn |

| Credit contraction magnitude | ~55% decline new lending | ~35% decline | 30-40% smaller |

| Unemployment peak | 26.3% (2013) | 18-20% (est.) | 6-8pp lower |

| Government bank bailout needs | €100bn EU/ESM program | €40-50bn manageable domestically | €50-60bn savings |

| Sovereign debt peak | 99% GDP (2014) | 60-70% GDP (est.) | 29-39pp lower |

With 30-40% less credit contraction, construction would have declined more gradually. Some projects would have obtained completion financing rather than halting entirely. Construction employment would have fallen less precipitously, containing unemployment increases. Lower unemployment would have preserved more tax revenue and required fewer unemployment benefits, improving fiscal balances.

However, this requires important qualifications. Waiving close links would have provided temporary liquidity relief, not permanent solvency. Spanish banks had extended excessive credit to unsustainable real estate development. Land prices quintupled (500% increase) between 1997 and 2007 while average housing prices more than doubled in real terms, both far exceeding reasonable relationships to income growth or demographic factors. Correcting these imbalances necessarily required substantial price declines and loan losses.

The fundamental constraint was the ECB’s inability to directly purchase impaired assets. The Treaty prohibits monetary financing, which ECB officials interpreted as precluding asset purchases that would transfer credit losses to the central bank’s balance sheet. Without legal authority for American-style QE, the ECB could provide liquidity through collateralized lending but not solvency by removing toxic assets.

Draghi’s “Whatever It Takes”: Too Late But Decisive

Summer 2012 saw the crisis reach its apex. In June, Spain requested ESM assistance for bank recapitalization up to €100 billion, acknowledging that national resources were exhausted. Spanish ten-year yields approached 7%—the bailout trigger level that had forced Greece, Ireland, and Portugal into programs. Italian yields spiked above 6%, threatening the Eurozone’s third-largest economy. Markets seriously contemplated monetary union dissolution.

ECB President Mario Draghi’s July 26, 2012 speech in London fundamentally altered the dynamics: the ECB would do “whatever it takes” to preserve the euro—”believe me, it will be enough.” Markets understood this as an implicit promise of unlimited sovereign bond purchases if necessary.

In September 2012, the ECB formalized this commitment through Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT), permitting unlimited sovereign bond purchases from countries in ESM adjustment programs. OMT was never actually activated—the announcement alone sufficed—but it broke the doom loop psychology. Spanish ten-year yields fell from nearly 7% to below 5% within months, eventually dropping below 3% by 2014.

OMT’s credibility rested on overcoming constraints that had paralyzed earlier ECB action. Article 123 TFEU prohibits monetary financing, which ECB officials had previously interpreted as precluding large-scale sovereign purchases. OMT circumvented this through conditionality: only countries in ESM programs with strict adjustment conditions could access OMT, and purchases would occur in secondary markets rather than direct government financing.

Spain proceeded with restructuring under ESM oversight. Authorities created Sareb, a bad bank absorbing impaired real estate assets. Between 2012 and 2014, Spain received approximately €41 billion from the ESM for recapitalization—substantially below the €100 billion authorized, as OMT’s market stabilization reduced actual needs. Surviving cajas merged into larger entities, many converting to conventional banks with private shareholders. Spectacular failures occurred, including Bankia—a merger of seven failed cajas that required a €23 billion rescue.

The Long Shadow and Unlearned Lessons

Spanish GDP didn’t regain pre-crisis levels until 2017—nearly a decade after the shock. Unemployment peaked at 26.3% in 2013 and remained above 20% through 2015 despite modest GDP growth. Youth unemployment exceeded 50%, triggering mass emigration. Over 20,000 Spanish PhD holders left the country seeking opportunities abroad—a “brain drain” threatening long-term growth prospects. Public debt peaked above 100% of GDP in 2014 versus 34% pre-crisis, fundamentally altering Spain’s fiscal position for a generation.

Spain’s protracted recovery illuminates the mechanics of credit-based economies in ways standard models fail to capture. Conventional economic models treating banks as passive intermediaries cannot explain why recovery took so long despite ECB interest rates near zero and eventual monetary accommodation. Credit creation requires adequate bank capital and functioning collateral chains at two levels: collateral that borrowers pledge to banks, and collateral that banks pledge to central banks. When both become impaired simultaneously, credit creation stops regardless of interest rates.

Spanish banks holding large non-performing loan portfolios faced regulatory pressure to maintain capital ratios, forcing them either to raise new capital (difficult with low profitability and uncertain asset quality) or reduce assets by shrinking lending. Banks also needed to conserve collateral for ECB refinancing given the destruction of their MBS portfolios. Even after public capital injections, Spanish banks couldn’t or wouldn’t lend at rates necessary for robust recovery.

Small and medium enterprises, heavily bank-dependent and lacking capital market access, suffered acute credit constraints. Investment remained depressed, productivity stagnated, and unemployment persisted at crisis levels through 2015.

The American Contrast

The contrast with America reinforces these observations. The Fed and Treasury acted decisively in 2008-2009, removing toxic assets through direct purchases and guarantees. Fed QE began immediately in December 2008, purchasing MBS that cleaned balance sheets while providing stimulus. American banks received forced TARP recapitalizations whether they wanted them or not; the 2009 stress tests established capital adequacy credibility. By 2010, U.S. banks had resumed normal lending; by 2011, GDP had recovered to pre-crisis levels.

The Spanish crisis demonstrates that institutional rules governing collateral and credit creation dominate macroeconomic outcomes in ways conventional theory fails to capture. The narrative portraying Spain as suffering from fiscal profligacy requiring austerity was backward. Spain entered the crisis with surpluses and low debt. The crisis originated in banking overextension into real estate, funded through wholesale markets and securitization dependent on functioning collateral chains.

When those chains broke after Lehman—partly due to ECB collateral framework rigidities—credit creation stopped, producing a depression. The depression destroyed tax revenues lowered Spanish bond value and required bailouts that transformed a banking crisis into a sovereign crisis.

Policy Choices, Not Economic Laws

ECB collateral rules, designed for normal times to protect the central bank’s balance sheet, became procyclical amplifiers during the crisis. The close links prohibition prevented pledging of self-originated securities. Rating thresholds created cliff effects where minor downgrades rendered large volumes of collateral ineligible. Mark-to-market requirements meant frozen secondary markets compounded collateral shortages even for fundamentally sound assets. Higher haircuts on peripheral sovereign bonds strengthened the doom loop.

These were substantive policy choices that shaped crisis dynamics, not immutable economic laws.

The Fed’s flexible approach—accepting broader collateral classes, expanding rather than contracting eligibility, and directly purchasing toxic assets—enabled faster recovery by preventing collateral shortages from destroying credit creation. Central banks face a fundamental crisis choice: protect balance sheets by maintaining strict collateral rules, or protect economies by accepting temporarily higher credit risk to maintain credit creation. The ECB chose the former; the Fed chose the latter. Outcomes reflected those choices: America recovering within three years, Spain enduring a nearly decade-long depression.

Between 2007 and 2015, Spain experienced a compression of possibilities that pre-crisis success had seemed to rule out. Unemployment quintupled from 8% to 26%. Public debt tripled from 34% to over 100% of GDP. Real wages stagnated for a generation. Young Spaniards entered adulthood during a depression, shaping political attitudes that fractured the post-Franco party system. Podemos emerged on the left, Ciudadanos challenged the center-right, and regional separatism strengthened, particularly in Catalonia. The European project became associated with imposed austerity and institutional rigidity.

These outcomes reflected not inevitable economic laws but specific institutional choices. The ECB could have acted differently in 2007 when it maintained strict collateral standards at the moment Spanish banks needed maximum access. Earlier easing might have provided breathing room for gradual adjustment. The ECB could have waived close links prohibitions during the crisis. Most fundamentally, the ECB could have conducted genuine QE in 2009-2010, purchasing impaired assets and transferring credit risk to its balance sheet, as the Fed did.

Those choices had consequences.

The credit system perspective reveals that central banks don’t merely set money’s price through interest rates. They define the boundaries of money creation through collateral frameworks, capital rules, and willingness to absorb credit losses. During Spain’s crisis, those boundaries contracted when expansion was most needed, transforming a manageable banking sector adjustment into a decade-long depression whose scars remain visible throughout Spanish society today.