The Common Misconception

Most people think central banks simply set interest rates and react to inflation. The reality is far more complex and consequential: central banks actively steer credit allocation across the economy through a sophisticated toolkit of instruments that determine who gets financing, at what cost, and for what purposes.

This isn’t a conspiracy theory or a criticism—it’s how modern monetary systems actually work. Understanding this machinery is essential for anyone trying to make sense of housing booms, corporate debt markets, or why small businesses struggle to access credit while large corporations get cheap funding.

The Central Bank’s Complete Toolkit

Central banks don’t just have one lever (interest rates)—they have at least eight distinct policy instruments that work together to shape credit conditions:

- Interest Rate Policy – The price of borrowing reserves

- Open Market Operations (OMO) – Temporary liquidity management

- Quantitative Easing (QE) – Large-scale asset purchases (several variants)

- Collateral Policy & Haircuts – Rules for what assets can secure borrowing and at what discount

- Standing Facilities – Emergency lending and deposit mechanisms

- Reserve Requirements – Minimum cash banks must hold

- Macroprudential Tools – Capital ratios, leverage limits, loan-to-value caps

- Forward Guidance – Communication about future policy intentions

Let’s examine how each works and, critically, how they work together.

Tool 1: Interest Rate Policy

What It Is

The central bank sets a target rate for overnight interbank lending (in the US: the Federal Funds Rate; in Europe: the Main Refinancing Operations rate). This becomes the benchmark that influences all other interest rates in the economy.

How It Works

Central bank raises rates

↓

Banks' cost of borrowing reserves increases

↓

Banks pass higher costs to customers

↓

Mortgages, business loans, consumer credit become more expensive

↓

Borrowing falls, spending decreases

↓

Economy slows, inflation moderates

The Limitation

Interest rates affect the PRICE of credit, but not necessarily the QUANTITY or ALLOCATION. If nobody wants to borrow (demand problem) or banks refuse to lend (supply problem), rate cuts may be ineffective—the classic “pushing on a string” problem.

Example: After 2008, the Fed cut rates to near-zero, but credit growth remained negative for years because banks were repairing balance sheets and households were deleveraging.

Tool 2: Open Market Operations (OMO)

What It Is

The central bank buys or sells securities (typically government bonds) to manage the quantity of reserves in the banking system.

Two Types:

Temporary OMO (Repo Operations):

- Central bank buys securities with agreement to sell them back in 1-14 days

- Temporarily injects liquidity

- Used for daily interest rate management

Permanent OMO:

- Central bank buys securities outright

- Permanently increases bank reserves

- Used for longer-term liquidity adjustment

How It Works

CB buys €10 billion in government bonds from banks

↓

Banks' reserve balances increase by €10 billion

↓

Banks have more capacity to lend

↓

Credit conditions ease (if banks want to lend and borrowers want to borrow)

Key Insight

This increases bank RESERVES, but whether that translates to real economy lending depends on bank decisions. The transmission is indirect and uncertain.

Tool 3: Quantitative Easing (QE) – Three Variants

Here’s where it gets interesting. Not all QE is the same, and the differences matter enormously.

QE Type 1: Conventional QE (Purchases from Banks)

What happens:

- Central bank buys long-term government bonds or mortgage-backed securities FROM BANKS

- Banks receive reserves in exchange

- This is similar to permanent OMO but larger scale and longer-duration assets

Transmission:

CB buys bonds from Bank A

↓

Bank A's reserves increase

↓

Bank A has lower funding costs

↓

Bank A MAY expand lending (their decision)

↓

Credit MIGHT flow to real economy (slow, uncertain)

Why it’s called “Fake QE” by some economists (like Richard Werner): The money goes to bank balance sheets, not directly into the economy. Banks can simply hold the reserves rather than lending them out. And it is basically the same as OMO.

Real-world example: Fed’s QE1-QE3 (2008-2014) injected $3.5 trillion, but much of it sat as excess reserves rather than becoming new loans.

QE Type 2: Crisis QE (Buying Bad Assets from Banks)

What happens:

- Central bank purchases non-performing loans or distressed assets from banks

- Primary goal: balance sheet repair, not stimulus

Purpose: Stabilize the financial system by removing toxic assets that prevent banks from lending. This is more about avoiding disaster than stimulating growth.

Example: US FED TARP program (2008) purchases during Global Financial Crisis (2008-2012).

QE Type 3: Direct QE (Purchases from Non-Banks)

What happens:

- Central bank buys corporate bonds, commercial paper, or even equities FROM COMPANIES or ASSET MANAGERS

- The seller receives a deposit at their commercial bank

- Money enters the real economy DIRECTLY, bypassing bank lending decisions

Transmission:

CB buys corporate bonds from Company X

↓

CB instructs Company X's bank to credit their account

↓

Company X now has cash deposits

↓

Company X can spend, invest, hire IMMEDIATELY

↓

Real economy effect is FAST and DIRECT

The central bank essentially replaces commercial banks in credit allocation. The CB decides which sectors and companies get liquidity.

Real-world examples:

- Bank of Japan: Purchased ¥50 trillion in equity ETFs, becoming the largest shareholder in many Japanese companies

- Federal Reserve (2020): Corporate bond facilities during COVID-19

- ECB: Corporate Sector Purchase Programme (€340 billion in corporate bonds)

The Critical Difference

| QE Type | Liquidity Goes To | Who Decides Credit Allocation | Speed to Real Economy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional (from banks) | Bank reserves | Banks decide | Slow, indirect |

| Crisis (bad assets) | Bank balance sheet repair | Banks decide (eventually) | Medium |

| Direct (from non-banks) | Real economy deposits | Central bank decides | Fast, direct |

Tool 4: Collateral Policy & Haircuts

This is one of the most powerful but least understood tools.

What It Is

When banks borrow from the central bank (or from each other in repo markets), they must pledge collateral—assets like government bonds, mortgages, or corporate loans. The haircut is the discount applied: a 3% haircut on a €100 million asset means you can only borrow €97 million against it.

Why This Matters Enormously

Here’s the key mechanism that’s often missed: Some (Bonds, MBS, ABS) newly created loans can IMMEDIATELY be used as collateral. The process is complicated and not entirely true for one loan, but banks issue many loans per day.

When a bank issues a mortgage:

- It creates a new deposit for the borrower (money creation “out of thin air”)

- The borrower spends that deposit, requiring the bank to transfer reserves to other banks

- The bank can pledge that new mortgage in the repo market to obtain the reserves needed

This means haircut policy directly affects lending capacity and direction, not just post-lending funding costs. Loan that have a high haircut are less interesting than loans having a low haircut.

Transmission Example

Scenario: Central bank reduces haircut on mortgages from 40% to 15%

Bank’s funding calculation:

Before (40% haircut):

- €100m mortgage can be used to borrow €60m via repo at 5% interest

- Remaining €40m must be funded with expensive equity/term debt at 8%

- Average funding cost: (0.60 × 5%) + (0.40 × 8%) = 6.2%

After (15% haircut):

- €100m mortgage can be used to borrow €85m via repo at 5%

- Only €15m needs equity/term debt funding at 8%

- Average funding cost: (0.85 × 5%) + (0.15 × 8%) = 5.45%

Result:

- Bank’s funding cost falls by 0.75 percentage points

- Bank can lower mortgage rates by ~0.5-0.75 percentage points (passing savings to borrowers)

- Housing demand increases

- House prices rise

This mechanism works in BOTH directions:

- Raising haircuts tightens credit instantly

- Lowering haircuts eases credit instantly

Real-World Impact

The ECB during the European sovereign debt crisis (2011-2012):

- Expanded eligible collateral and reduced haircuts on sovereign bonds from peripheral countries

- Prevented funding freeze for banks in Greece, Italy, Spain

- Without this, banks in those countries would have lost access to liquidity entirely

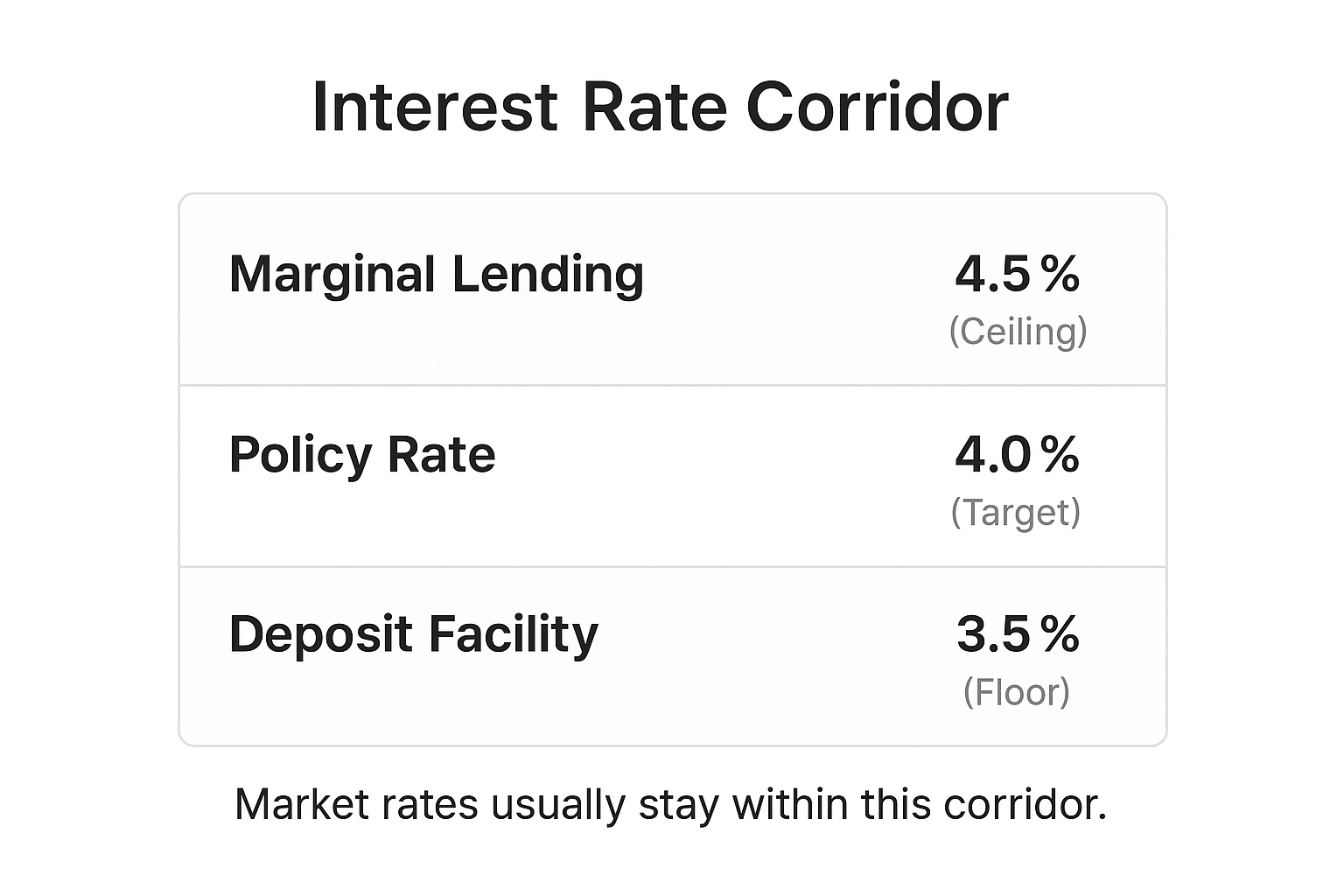

Tool 5: Standing Facilities (The Interest Rate Corridor)

What They Are

Two automatic facilities that create boundaries for market interest rates:

Marginal Lending Facility (Discount Window):

- Banks can borrow reserves ON DEMAND overnight

- Rate is ABOVE the policy rate (e.g., policy rate + 0.5%)

- Acts as CEILING for interbank rates (no bank pays more than this)

Deposit Facility:

- Banks can deposit excess reserves with CB ON DEMAND

- Rate is BELOW the policy rate (e.g., policy rate – 0.5%)

- Acts as FLOOR for interbank rates (no bank lends below this)

The Corridor System

Why This Matters

This system ensures:

- Payment system always functions (banks can always get reserves if needed)

- Interest rates stay near target automatically

- Financial stability backstop exists

Tool 6: Reserve Requirements

What It Is

Banks must hold a minimum percentage of customer deposits as reserves at the central bank.

Example:

- 2% reserve requirement

- Bank has €1 billion in deposits

- Must hold €20 million in reserves

Current Status: Declining Importance

Many central banks have reduced or eliminated reserve requirements:

- United States: 0% since March 2020

- Eurozone: 1% (down from 2%)

- UK: No mandatory requirements

- Canada: Eliminated in 1992

Why the Decline?

- Interest rate targeting is more precise than quantity-based rules

- Massive QE created excess reserves, making requirements irrelevant

- Macroprudential tools are more targeted and effective

Modern role: More of a stability safeguard than an active policy tool.

Tool 7: Macroprudential Tools

These are regulatory measures to prevent systemic risk and excessive credit booms.

Key Instruments:

1. Capital Adequacy Ratios

- Banks must hold equity equal to 8-13% of risk-weighted assets

- Higher capital = safer banks but less lending capacity

2. Leverage Ratios

- Total capital / total assets (unweighted)

- Typically 3-5% minimum

- Prevents balance sheet size growth regardless of asset “safety”

3. Loan-to-Value (LTV) Limits

- Maximum loan as % of property value

- Example: 80% LTV cap means 20% down payment required

- Directly constrains household borrowing capacity

4. Debt-to-Income (DTI) Limits

- Maximum debt service as % of income

- Example: 40% cap means monthly debt payments can’t exceed 40% of income

- Ensures borrowers can afford repayments

5. Countercyclical Capital Buffers

- Increased during booms (0% → 2.5% of assets)

- Released during downturns

- “Lean against the wind” policy

How These Tools Steer Credit

Example: Housing Boom Control

New Zealand (2013-2021):

- Implemented strict LTV limits for Auckland property

- Required 40% down payment for investors

- Result: Housing credit growth slowed significantly, price increases moderated by estimated 15-20%

Example: Targeted Sectoral Limits

Many countries apply higher risk weights (requiring more capital) to commercial real estate lending while maintaining lower weights for residential mortgages. This steers credit from commercial to residential property.

The Crucial Distinction: LTV vs. Haircuts

| Concept | LTV Limit | Collateral Haircut |

|---|---|---|

| Applies to | Household borrowers | Banks borrowing from CB |

| Controls | How much household can borrow | How much bank can fund with collateral |

| Example | Max 80% LTV = borrower needs 20% down payment | 15% haircut = bank gets 85% of asset value in funding |

| Targets | Household leverage | Bank/institutional leverage |

| Timing | At loan origination | Continuously in funding markets |

Both constrain leverage but at different points in the system.

Tool 8: Forward Guidance

What It Is

Central bank communication about likely future policy path.

Examples:

- “Interest rates will remain low for an extended period”

- “We will not raise rates until inflation exceeds 2% for sustained period”

- “We expect to keep asset purchases at current pace through 2024”

Why It Works

Influences expectations, which affect:

- Long-term interest rates TODAY

- Investment and spending decisions TODAY

- Inflation expectations (self-fulfilling to some extent)

Real impact: When the Fed signals “higher for longer” on rates, mortgage rates rise immediately even before any rate hike occurs.

How Tools Work Together: Coordination Creates Amplification

The real power comes from deploying multiple tools simultaneously. The combined effect is often greater than the sum of individual tools—what economists call complementarity.

Example 1: Maximum Stimulus (COVID-19 Response, March 2020)

Federal Reserve coordinated package:

1. Cut interest rates to 0-0.25% (cheapest reserves ever)

2. Launched $120bn/month QE (flood system with reserves)

3. Reduced haircuts across all collateral (easier to obtain funding)

4. Created emergency lending facilities (TALF, CPFF, etc.)

5. Forward guidance: "rates low until 2023" (anchor expectations)

Result:

- Financial markets stabilized in WEEKS (vs. years in 2008)

- Credit markets reopened almost immediately

- Corporate bond spreads collapsed

- Economic recovery began faster than any previous crisis

Why so effective? Each tool reinforced the others:

- Low rates made borrowing cheap

- QE ensured reserves were abundant

- Reduced haircuts meant banks could leverage those reserves

- Emergency facilities provided backstop confidence

- Forward guidance prevented expectations of imminent tightening

Example 2: Targeted Housing Cooling (Multiple Countries, 2010s)

Central banks wanting to cool housing without crashing economy:

1. Keep policy rates low (support overall economy)

2. Increase haircuts on mortgages (make mortgage funding expensive)

3. Tighten LTV limits (limit household borrowing)

4. Raise capital requirements on mortgages (make mortgage lending less attractive)

5. Keep QE focused on corporate bonds (support business investment)

Result: Credit reallocated from housing to business sector without overall credit contraction.

Examples:

- Sweden: Mortgage amortization requirements dampened housing leverage

- New Zealand: LTV limits cooled Auckland housing boom

- Canada: Mortgage stress tests slowed housing credit growth

Example 3: Crisis Prevention (2022-2023 Tightening)

Federal Reserve coordinated tightening:

1. Raised rates 525 basis points in 18 months (fastest hiking cycle in 40 years)

2. Quantitative Tightening: $95bn/month (drain reserves)

3. Stricter bank supervision after SVB failure (implicit tightening)

4. "Higher for longer" messaging (prevent premature easing expectations)

Result:

- Mortgage rates jumped from 3% to 7.5% in under 2 years

- Credit conditions tightened dramatically

- Bank lending growth collapsed

- Inflation fell from 9% to 3%

Caution: This combination was SO effective it created financial stress (regional bank failures, commercial real estate concerns).

Who Wins and Who Loses: The Distributional Consequences

Understanding the toolkit reveals that central bank policies are NOT neutral—they create clear winners and losers.

Winners from Accommodative Policy (Low Rates + QE):

1. Asset Owners

- QE raises prices of stocks, bonds, real estate

- Wealth gains concentrated among top income quintiles

- Capital gains accrue to those already wealthy

2. Borrowers (Especially with Collateral)

- Lower interest rates reduce debt service costs

- Homeowners refinance at lower rates

- Corporations roll over debt more cheaply

3. Large Corporations

- Direct QE (corporate bond purchases) provides cheap funding

- Access to capital markets improves

- Can issue debt at historically low rates

4. Financial Sector

- Trading profits from volatility

- Fees from increased transaction volumes

- Cheap funding (when yield curve is steep)

Losers from Accommodative Policy:

1. Savers and Retirees

- Low interest rates reduce income from deposits

- Bond yields fall

- Pension funds struggle to meet obligations

2. Renters and Non-Asset Owners

- Housing price inflation reduces affordability

- No compensating wealth gains

- Higher rents without asset appreciation

3. Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs)

- Limited access to QE benefits (bonds not purchased by CB)

- Depend on bank lending (indirect, slower channel)

- Face increased competition as large firms gain funding advantage

4. Future Generations (Potentially)

- Debt accumulation may constrain future fiscal space

- Asset bubbles may burst, creating future crises

- Intergenerational wealth transfers via housing prices

The Inequality Effect

Empirical evidence:

- US/UK/EU QE programs: Top 10% wealth holders captured 50-70% of asset price gains

- Housing wealth: Homeowners’ wealth increased 20-40% in many markets (2010-2020)

- Non-asset-owners: Real income grew <10% over same period

The paradox:

- Accommodative policy REDUCES income inequality (supports employment)

- But INCREASES wealth inequality (asset price inflation)

- Net effect depends on which you weight more heavily

The Big Picture: Central Banks as Economic Architects

What We’ve Learned

1. Multiple Dimensions of Control Central banks don’t just set “the interest rate”—they control at least 8 distinct policy dimensions that can be adjusted independently.

2. Direct Credit Allocation Through tools like Direct QE, differentiated haircuts, and targeted lending facilities, central banks effectively determine which sectors receive financing.

3. Powerful Interaction Effects Coordinated deployment creates amplification—total impact exceeds sum of individual tools.

4. Significant Distributional Impact Policies systematically favor asset owners over non-owners, large corporations over SMEs, and collateral-rich borrowers over others.

The Central Question

If central banks can actively steer credit allocation, asset prices, and wealth distribution through this multi-dimensional toolkit, this raises fundamental questions:

Technical:

- How should multiple tools be optimally combined?

- What are the right trade-offs between objectives?

Institutional:

- What governance structures ensure accountability?

- Where should boundaries be between monetary policy, fiscal policy, and industrial policy?

Democratic:

- Should unelected officials make decisions that affect wealth distribution?

- How do we balance technocratic expertise with political legitimacy?

The Reality

Central banks are not passive institutions that merely respond to inflation. They are active architects of the monetary system, making decisions that fundamentally shape:

- Which economic activities receive financing

- How wealth is distributed across society

- The balance between housing investment and productive investment

- The leverage and fragility of the financial system

Understanding this toolkit is essential for:

- Investors – anticipating policy impacts on asset prices

- Business leaders – navigating credit conditions

- Policymakers – designing appropriate governance

- Citizens – participating in informed democratic debate about central bank power

The question is no longer WHETHER central banks steer the economy, but HOW they should use this power, subject to what constraints, and with what accountability mechanisms.

Further Reading

On QE distinctions:

- Richard Werner’s work on QE1 vs. QE2

- Krishnamurthy & Vissing-Jorgensen (2011) on QE effectiveness

On collateral policy:

- Gersbach & Althanns (2023): “The Monetary Policy Haircut Rule”

- Nyborg (2017): “Central Bank Collateral Frameworks”

- Fang et al. (2020): “Collateral-Based Monetary Policy: Evidence from China”

On macroprudential tools:

- Cerutti, Claessens & Laeven (2017) on effectiveness of macroprudential policies

- Case studies from New Zealand, Sweden, Canada on LTV limits

On distributional effects:

- Studies on wealth inequality impacts of QE in US, UK, and Eurozone

- Household-level data analysis of monetary policy impacts

This article synthesizes research from monetary economics, central banking operations, and financial market studies to provide a comprehensive overview of how central banks actively shape credit allocation and economic outcomes. The mechanisms described are based on actual central bank operations and documented transmission channels.